The Personal Documentary Considered In ‘The Cinema of Me’

By Mary Moylan

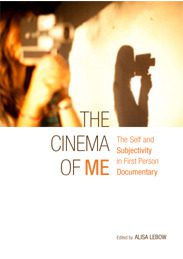

The construction of subjectivity in first-person documentary is given serious consideration in The Cinema of Me: The Self and Subjectivity in First Person Cinema, a collection of first-person essays from several talented film theorists and practitioners. These essays examine the roles of geopolitical contexts, ethnicity, cultural identities and personal histories, and offer a timely understanding of this documentary sub-genre. Special attention is given to the fact that first-person films are often not a cinema of “me,” but of someone else who informs the filmmaker’s sense of him or herself. Or, the focus of the subject may be about an event or community. First and foremost, though, we are reminded that first-person filmmaking is about a mode of address. And whether a first-person film does this speaking in singular or plural voice is the concern for this book.

Alisa Lebow, a filmmaker and professor at Brunel University in the UK, offers in her introduction to this volume an explanation of this discerning inquiry into first-person film. And, noting the formal dualism inherent within the first-person grammatical structure—the “I” inheres the “we”— Lebow shares some of her inspiration from film theorist Jean Luc Nancy. Pointing to the formulation of the “singular plural,” Nancy clarifies that the “‘I’ does not exist alone, but always with ‘another.'”

Lebow’s style is one of sharp philosophical distinctions—namely, one that regards the matter of knowing ourselves as both a central ontological question and an exploration of self-representation. With an insightful reflection into this connection between first-person filmmaking and language, she asserts, “The grammatical reference reminds us that language itself, though spoken by an individual, is never entirely our own invention, nor anyone else’s. Despite the fact that we believe it to express our individuality, it nonetheless also expresses our commonality, our plurality, our interrelatedness with a group, a mass, a sociality, if not a society. This is as true about the expression of individuality and subjectivity in first-person films as it is in language itself.”

First-person address in film was apparent mostly in avant garde cinema up until the 1980s, due in part to ideals of disinterested objectivity, according to Lebow; the emergence of the subjective voice in documentary had been suppressed. Since then, she notes, first-person filmmaking has gained a steady momentum.

In a valuable survey of the last decade of first-person cinema and its concerns in the scholarly field, Lebow points to University of Southern California professor Michael Renov, who takes autobiography as his starting point. The question of subjectivity as an organizing principle is credited to Australian National University professor David MacDougall, while analysis of individual modes of address such as the essay film goes to Laura Rascaroli of University College Cork in Ireland; vernacular video to Jon Dovey of the University of the West of England; and home movie to writer James Moran. Further designations include domestic ethnography (Catherine Russell), and performativity (Stella Bruzzi). Lebow claims that the term “first person” is uniquely able to include and incorporate the range of these related, yet distinct, practices.

This volume of essays is distinguished from other studies in several ways. First, this survey is international in scope and asks, What are the conditions for the emergence of the first-person mode of address in various parts of the world, and what are the consequences? The Cinema of Me looks at the emergence of first-person practices on the Internet, noting the complexities of an integrated, embodied subjectivity. And, though the breadth of this volume is wide, the depth is not compromised, as each essay treats theory in challenging and innovative ways.

The book further asks, What is the nature of the interplay between the individual and culture, and how is this tension played out in representational terms? How, or in what ways, can culture and ethnicity, for example, be said to construct the first-person character on screen? In what contexts and for what reasons do we find first-person filmmaking flourishing, and where is it still an unknown and unwelcome practice?

This book is divided into four sections: “First Person Singular,” “First Person Plural,” “Diasporic Subjectivity” and “Virtual Subjectivity.” The “First Person Singular” section includes several reflexive essays in which the filmmaker’s own subjectivities are represented in relation to their wider collectivities. Here, the authors discuss their own first-person films. Michael Chanan, filmmaker and professor at Roehampton University in the UK, offers in his essay “The Role of History in the Individual: Working Notes For a Film” a biographical investigation of his maternal grandmother’s cousin, Solomon Abramovich Trone, in his film The American Who Electrified Russia. Chanan refers to philosopher Walter Benjamin, who spoke of “the enigmatic question of the nature of human existence as such, but also of the biographical historicity of the individual.” While simultaneously constructing a dialogue between family memory and the archive, the film addresses the public and private, through their photographs and films, documents and mementos, and Chanan makes special note of the gaps discovered between them. As reflected in the title, this essay reads like a reflective diary and an insightful meditation on the process of the making of this film. Chanan wanted to make a film that foregrounded these problems and gaps by presenting the process of the investigation.

The “First Person Plural” section, according to Lebow, enters fraught territory, wherein the films referenced here find a circuitous route to self -representation. In Sabeena Gadihoke’s essay “Secrets and Inner Voices: The Self and Subjectivity in Contemporary Indian Documentary,” she examines, among other films, Shohini Ghosh’s Tales of the Night Fairies, which the author describes as reflecting a kind of deconstruction of the first person. Further, the filmmaker is regarded as positioning her subjects as a “series of surrogate selves.” Gadihoke lists a number of developments that emerged in the 1990s in India that served to usher in a vibrant independent documentary movement–namely, the dismantling of a traditional model of state control over cultural production, and the economic liberalization that brought about radical changes in the Indian media through satellite broadcasting, the Internet and the digital revolution.

The “Diasporic Subjectivity” section takes diasporic identities as its organizing principle. Lebow’s essay, “The Camera as Peripatetic Migration Machine,” makes a claim for the self-reinforcing nature of cine-documentation, with its ability to mobilize geographical shifts, while only appearing to record them. Here, Lebow examines three films identified within the area known as transnational documentary: Fotographias (Andres Di Tella, Argentina/India, 2007); I for India (Sandhya Suri, UK/India, 2005); and Grandma has a Video Camera (Tania Cypriano, US/Brazil, 2007).

“Virtual Subjectivity,” the final section of The Cinema of Me, examines the emergence of virtual identities and the implications they have on contemporary self-representation. Peter Hughes, who teaches communications at La Trobe University in Australia, provides a grounded sociological treatment of the emergence of the social networking technologies, or Web 2.0. This essay reflects the changes in media structures and cultures as the shift from the broadcast-based mass communication model gives way to the fragmented and more fluid models in the wider range of media forms. Hughes makes a claim for regarding new developments such as participation, personalization and fragmentation as some of the main characteristics of Web 2.0 that provide the contexts of production and reception for documentary.